Mary Leoson

Leoson’s Research Question:

How can creative writing instructors use multimodality and narrative-based community-building to maximize inclusion in writers’ workshops?

Image: Canva Pro

Most creative writing classrooms, particularly at the MFA-level, adhere to a form of critique that involves silencing the writer while peers discuss his/her/their work in front of them. The goals are to provide constructive criticism to the writer and to reflect the ways in which a piece is received without the writer’s explanation or defense of the work. Critics of this model suggest that silencing the writer can result in feelings of shame, hopelessness, and frustration, both for the writer and for other participants.

Some are satisfied with the workshop model and see no need to change. I am not suggesting that there is no value in the model. After all, it helped me develop a thicker skin when it comes to criticism. However, I did not graduate from my MFA program unscathed. It was this experience with being silenced, and watching others being silencing, that I began to question the approach. What I found is that the conversation is complicated, but it is brewing across the United States and internationally.

I have taken the position that asking writers to participate in the traditional workshop model without providing alternatives may cause more harm than good. I realize there are instructors who will disagree with me, however, I feel it is important to consider ways to augment the traditional approach to foster a more inclusive space. If instructors do not create a safe environment for writers to present and discuss their work, this may result in wounding students emotionally and psychologically, even if their writing improves and they are offered publishing deals. This may be particularly damaging to those who have been marginalized or have been through prior trauma. Creative writing training programs may earn bragging rights about graduates, but at what cost?

Criticism of the traditional writers’ workshop model is growing and many teachers are looking for ways to be more inclusive. Much of the pedagogy that guides creative writing classrooms is MFA-guarded knowledge that reflects a white, cisgendered, heteronormative male-led tradition; there is a lack of progressive pedagogy and cultural sensitivity with the current predominant structure, but there is a growing body of research that contains more inclusive strategies (Chavez 9-10, Salesses 6-7). While some of these published strategies, such as those in books like The Anti-Racist Writers Workshop and Craft in the Real World, include practical activities and tactics, there is a need for more. Specifically, there is a need for strong community-building practices within creative writing spaces and diverse ways for students to express their perspectives and mastery of writing principles.

One promising approach to this problem is combining pedagogies that foster a sense of belonging and help students establish communication norms based on equity and dignity with options for multimodal composition. This multifaceted approach may significantly fill the gap between the need for inclusive practices and emerging theoretical approaches that seek to support writers of color, differently abled writers, those from the LGBTQIA+ community, those with learning challenges and mental health disorders, and students who have experienced othering or have been through trauma. Through a multimodal means, writers can move from being silenced to embracing their voices, not only in alphabetic texts but also in images, videos, song, drama, dance and physical movement, spoken word, and more. And if students are provided with opportunities to connect with each other in nonjudgmental ways, based on mutually agreed upon community norms, their creative growth may be even more supported than it would be without attention to these social needs.

I am personally interested in this combined storytelling, multimodal, and community-building approach to the traditional writers’ workshop for several reasons. First, as a college level instructor of 15 years, I have seen community-building pedagogies foster connections among students so that their emotional and social growth aligns with that of their intellectual growth. Having been trained through organizations such as Facing History & Ourselves, The Institute for Life Coach Training, and the Northwest Narrative Medicine Collaborative, I have learned to introduce activities that help students form cohesive, collaborative learning communities in which they feel safe and respected. Second, I have also seen multimodal teaching and learning strategies appeal to diverse student groups, including those of color, learners from other marginalized communities (including both LGBTQIA+ and veteran populations), neurodivergent students, students who possess particular forms intelligence and learning style preferences, those who identify as creative (and who are often “othered” for various reasons, including eccentricity), and students who have been through trauma. While my approach to multimodality in the past was limited to art projects, fliers, musical composition, drama, and animated powerpoint presentations, my recent training through the Digital Media and Composition Institute at The Ohio State University has only served to strengthen my position that multimodal projects can be helpful in appealing to a wider variety of students and yield a more inclusive classroom.

Third, as a graduate of an MFA Program that used only one style of workshopping creative pieces, the traditional writers’ workshop in which the writer is silenced, I can attest to the potential harmful results. This practice requires the writer to listen to feedback from peers while not being allowed to speak. In fact, the writer in some workshops is not even referred to by name (“the writer” or “the author” only) and peers often pretend the writer is not even in the room so they can honestly discuss the piece. He/she/they cannot defend the work or themselves, answer questions, or ask questions at this time. I have seen writers of color, LGBTQIA+ writers, and those who have been through trauma, be emotionally wounded and creatively stunted first-hand during this process. In fact, as one who has been through trauma surrounding my own writing, I felt this negative impact in workshop situations as well. My training through Florida State University in Trauma-Informed Pedagogy has only strengthened my position that instructors of all subjects and levels should be educated about how to manage potentially triggering academic environments. It is important to note here that trauma-informed pedagogy does not involve therapy of any kind, but rather holds instructors accountable for recognizing when students are distressed, or may be triggered, and adjusting appropriately.

While the traditional writers’ workshop can help writers develop “thicker skin” and help them understand how their writing is being received, these benefits come with a serious cost for many students. There are other approaches, such as those suggested by Chavez in The Anti-Racist Writers Workshop, Salesses in Craft in the Real World, and Lerman in Critique is Creative: The Critical Response Process in Theory and Action. As a creative writing teacher, I owe it to my students to put these culturally responsive approaches into action. I also aim to share my findings and recommendations with other instructors via this collaborative website.

Leoson, Mary. “Positionality Art: My Perspective.”

Leoson’s Positionality Statement

My intention in discussing inclusion in the classroom is both to ensure that my own pedagogical practice results in fair and empathetic treatment of students and to help others examine their own practices in support of student success. As a white, cisgender, middle-class woman, I am aware that my privilege may result in blind spots in society and in my classroom. I am committed to continuous growth and bringing my own unconscious biases to light. Because this is a process, I must engage in self-reflection, actively listen to others to deepen my understanding of differences and marginalization, and engage in uncomfortable conversations to effect positive change in myself and in my community. Through this project, I hope to deepen my understanding of the equity challenges inherent in college level creative writing classrooms while uplifting voices of those whose scholarship has revealed the kinds of changes needed to achieve equity and inclusion in English courses. My hope is that this project amplifies the work done by writers of color and other marginalized scholars so that awareness of power disparities continues to grow in the creative writing community.

Additionally, I aim to shed light upon the importance of considering past student trauma in the classroom, which may stem from prejudice, discrimination, domestic violence, emotional/psychological abuse, experiences in war, or other extreme situations. While I cannot understand first-hand the trauma people of color or those from the LGBTQIA+ community have experienced, I do know what it feels like to endure emotional abuse connected to writing as well as marginalization when it comes to religion and parental/marital status. I hope that these experiences humbly inform my approach to this project and serve to remind me that trauma, in all its many forms, can yield a multitude of challenges. I also know, however, that it can deepen one’s ability to have compassion for others. Additionally, as a trained life coach and narrative medicine facilitator who also teaches psychology at the college level, I believe some helpful adjustments can be made in the classroom when considering trauma-informed pedagogy and community-building. My voice is but one in a vast sea, but I hope it adds to this conversation in a helpful and insightful manner.

Connection to Story-Based Pedagogy

My area of focus connects to story-based pedagogy first in the way it relates to respecting various aspects of diversity and is influenced by Culturally Responsive Teaching, Trauma-Informed Pedagogy, and Narrative Medicine Pedagogy. From the Culturally Responsive Teaching perspective, both Chavez (The Anti-Racist Writers Workshop) and Hammond (Culturally Responsive Teaching) stress how vulnerability and storytelling can be used to foster connections among students and support inclusivity in the classroom. If students are presented with others’ stories, they can begin to empathize with the ways their experiences have shaped their worldviews. In turn, they can also share their own experiences from a place of authenticity. Trauma-Informed Pedagogy stresses that it may benefit students when instructors look for shifts in behavior, such as the fight/flight/freeze response in them, and they respond effectively and with compassion (Wuest and Subramaniam 17-18). Such responses should support a student’s “capacity for self-regulation” (Wuest and Subramaniam 17). And while narrative medicine is an approach that was developed initially to educate medical students, its pedagogy may be successfully applied to any group of people working together, including college students. In the narrative medicine approach, third objects (i.e., pieces of writing, works of art, or musical selections) may serve as a neutral ground for discussing subjective perspectives, experiences, and participants’ views (Charon et al. 162). The idea is to help students connect with each other, even when their opinions diverge, and to foster helpful communication norms, “non-judgmental listening,” and empathy (Charon et al. 162).

The second way it relates to story-based pedagogy involves classroom activities and assignments themselves, which can be intentionally designed for community-building. The act of producing stories (fiction, nonfiction, or in poetry form) is at the center of all creative writing classes, but there are also opportunities for storytelling as students get to know each other, as they explore their own relationships to the writing process, as they consider alternative viewpoints and possibilities for revision, and as they offer feedback to each other in writers’ workshops. Please see Figures 1, 2, and 3 below, which I designed to illustrate some of these possibilities.

Figure 1. Storytelling to build community and explore the self in creative writing classrooms.

Figure 1 shows that while students’ creative pieces sit at the center of the Venn Diagram and are the culminating projects within the course, along the way, they can engage in storytelling to strengthen interpersonal connections and become more aware of their own identities as writers. Stories can be used to build community by fostering positive interpersonal dynamics among participants, discovering shared value, learning about differences, deepening understanding about what it means to treat others with dignity, defining ideas about craft and genre, and by using “third objects” to engage in collaborative analysis (Chavez 7, Salesses 30, Charon et al. 162). Opportunities for engaging in these activities include multiple modes, such as sharing food, student-selected prompts, music, and games; oral presentations or digital stories that reflect values statements; animated letters to peers expressing gratitude and/or apologies if appropriate; collaboratively analyzed or co-created pieces; and designed infographics that reflects student-defined terms and community expectations (Chavez 54-56, Charon et al. 162).

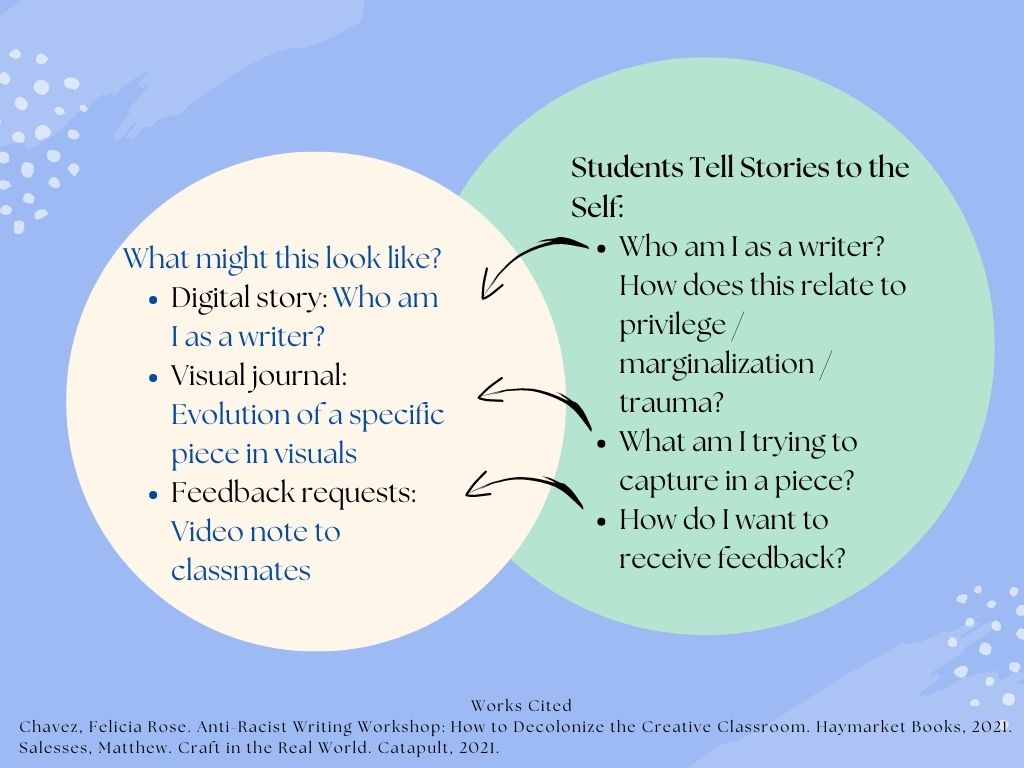

Figure 2. Examples of storytelling assignments to build community in creative writing classrooms.

Students can also use multimodal forms of storytelling to express and discover things about themselves as writers. Students might create a digital story in response to the question: Who am I as a writer? They might utilize a visual journal to track the evolution of a creative piece or brainstorm about possibilities for that piece. They might also consider creating a short video or audio note to let peers know their preferences for receiving feedback and/or their intentions for a piece (artist’s statements). Additionally, facilitators can lead students through narrative medicine-inspired activities in which all participants collectively analyze a poem, visual image, or piece of music that is not produced by one of the class members; the “third object” can serve as a neutral item for analysis that helps participants practice listening, witnessing another’s viewpoint, and responding to each other with dignity and empathy (Charon et al. 162-163).

Figure 3. Storytelling for writers to explore their own identities and experiences in creative writing classrooms.

While storytelling may happen in more traditional ways based on the Figures above, they may also include additional multimodal messages, such as infographics, podcast conversations, videos, digital stories, collectively produced collages or lists of values, and by incorporating the senses in other ways (i.e., food, music, dance, dramatic games). Storytelling and multimodality can also be combined to address some of the problems inherent in the traditional writers’ workshop, some of which include criticisms over silencing the writer and the notion that predominant opinions may reflect a privileged, white, cisgendered male perspective on craft (Chavez 9-10, Salesses 6-7). Story in text and in other modes, such as visual art, music, and film, can help participants empathize with each other and varying world views when they are created by the participants or when they are neutral “third objects” being analyzed (Charon et al. 162-163).

Writers can express their ideas through multimodal and digital mediums in order to provide personal background (identity as a writer and purpose), context regarding the piece of creative writing to be workshopped, and the author’s vision for its creative evolution. Storytelling, therefore, is not only a student product at the end of the course but becomes part of the communal process in the classroom, as students work to understand each other and each other’s work. Reflection upon the writing process (story of one’s relationship to the creative piece’s evolution), the analysis of neutral “third objects”, and as an extension of the student-produced story itself into other modes can also be added over the course of the semester. This approach requires storytelling at every level and in various modes, with the intention that these activities support individual student growth in creative writing, his/her/their connection to community and each other, and a deeper awareness of the stories we tell ourselves—about ourselves, about others, and about the storied products. Additionally, if instruction includes careful attention to self-reflection when witnessing others’ stories, students may gain insight about their implicit biases and communication patterns so that they can move toward empathy rather than shame or judgment.

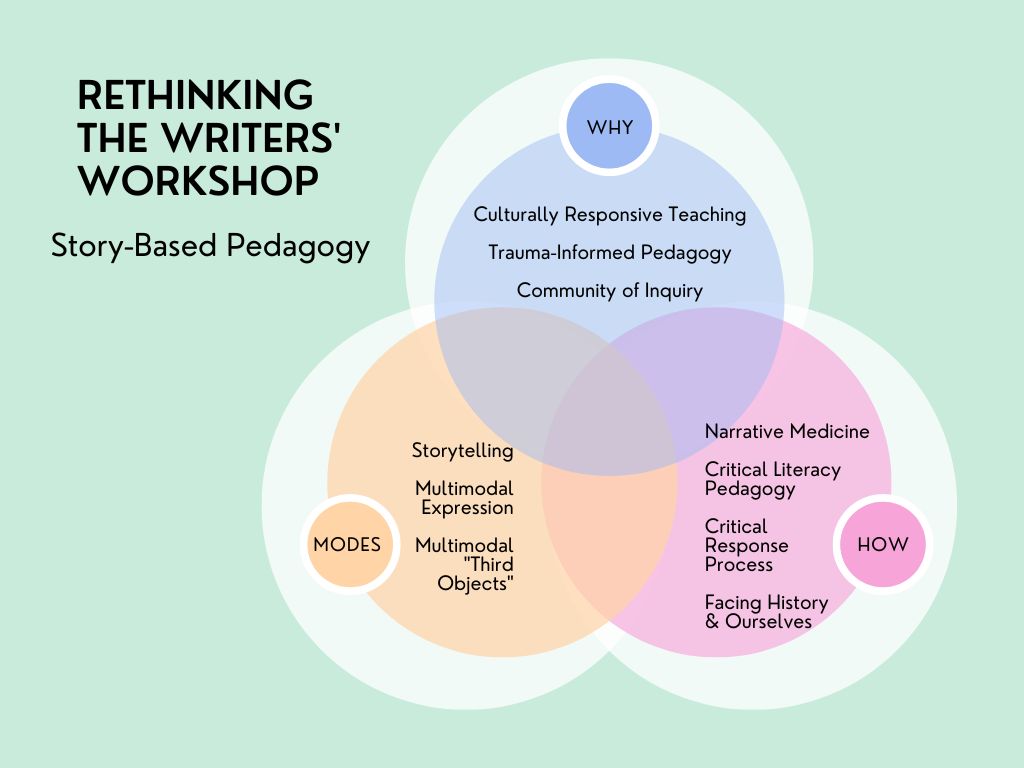

Figure 5. Rethinking the Writers’ Workshop – Why, How, and Modes

The case is made in the following literature review for rethinking the traditional writers’ workshop model because it is outdated, includes unfair power dynamics, and lacks attention to factors of diversity, trauma, and inclusivity. Figure 5 (above) shows how program directors and teachers can use the ideas presented here to examine current practices in writing workshops. It illustrates ways these ideas connect based on why change is needed, how it might look different, and what multimodal storytelling may empower students to produce.

Culturally Responsive Teaching, Trauma-Informed Pedagogy, and the Community of Inquiry Framework provide a rationale for shifting this antiquated model. First, Culturally Responsive Teaching calls our attention to the need to consider the context from which a student is entering the classroom, including ethnic background and self-identity (Hammond 17-20). It encourages examination of biased thinking and communication, both at the conscious and unconscious levels (Hammond 17-20). Trauma-Informed Pedagogy shines a light on the potential for damage that can be inflicted on workshop participants, either through re-traumatization, triggering prior wounds, or inflicting new ones (Wuest and Subramaniam 17-18). The Community of Inquiry stresses the importance of social presence in any classroom so that students may feel a sense of belonging and successfully contribute to the conversation (The Community of Inquiry). Now that teachers understand why we must make some changes, we turn our attention to how we can do this.

Narrative Medicine, Critical Literacy Pedagogy, the Critical Response Process, and Facing History & Ourselves all provide practical strategies for moving classrooms toward inclusivity and away from unfair power dynamics. Narrative Medicine offers opportunities for collaborative inquiry through the examination of “third objects”; this type of activity is a chance to set some ground rules for student engagement and to address any problematic behavior before students begin to examine their own work (Charon et al.163). Critical Literacy Pedagogy encourages the connection with text but also constructive criticism of it; the invitation to “restory” can reveal ways in which a piece might leave out marginalized voices or include stereotypes (Borsheim-Black et al. 24). The Critical Response Process places the writer-artist at the center of the conversation, empowering him/her/them to guide the conversation themselves and retain the power (Lerman and Borstel 30). Finally, Facing History & Ourselves offers training in facilitating difficult conversations that often bring up emotional and ethical questions (Facing History & Ourselves). If instructors can engage students in thoughtful conversation that maintains the dignity of all, but also bravely move into discussing diverging points of view and potential problematic messaging in texts, they may pave the way for more productive conversations when students begin workshopping their own writing.

Creative writing workshops have traditionally focused on the written page, which makes sense because that is why most students enroll in creative writing courses. However, storytelling as a process is more than just words on a page—it can be expressed orally, or through movement, song, collage, conversation, or food. Multimodal projects can bolster the creative process and foster higher-order thinking in students while they develop skills in the areas of audience and purpose, narrative function, conceptual organization, and relational learning (Lemerond 2, Stukenberg 1-2). Welcoming these other modes of expression and encouraging storytelling not only as a final product, but also as a process of interpersonal connection and self-reflection, may be one of the most powerful ways to build community and foster an inclusive space. Multimodal storytelling and narrative-based community-building may not be complete solutions to all the issues that have arisen from the traditional writers’ workshop, but they can certainly offer a foundation from which more growth toward inclusivity can spring.

For an interactive discussion about rethinking the writers’ workshop, please listen to episode four of our podcast, “Teaching With Story.”

Literature Review & Theoretical Foundation

View as a Flipbook from Heyzine: Theoretical Foundation Flipbook

Download as a .pdf file: Theoretical Foundation .pdf

Reflections & Insights

Co-Creating Dynamic, Brave Learning Spaces

View the presentation slides: Co-Creating Dynamic, Brave Learning Spaces

Telling Stories to the Self First

View the presentation slides: Telling Stories to the self First

Telling Stories to Build Community

View the presentation slides: Telling Stories to Build Community

Professional Development Opportunities

Narrative Medicine Facilitator Training: Northwest Narrative Medicine Collaborative

Diversity & Teaching Training: Facing History & Ourselves

Positive Psychology Training: The University of Pennsylvania’s Positive Psychology Center

Trauma-Informed Training: Florida State University’s Professional Development Offerings

Learn about the Community of Inquiry

Learn about Culturally Responsive Teaching

Culturally Responsive Teaching Strategies from Northeastern University

Works Cited

Borsheim-Black, Carlin et al. “‘Critical Literature Pedagogy: Teaching Canonical Literature for Critical Literacy.” Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, vol. 58, no. 2, 2014, 123-133.

Charon, Rita et al. “Racial Justice in Medicine: Narrative Practices Toward Equity.” Narrative, vol. 29, no. 2, 2021, pp. 160-177.

Chavez, Felicia Rose. Anti-Racist Writing Workshop: How to Decolonize the Creative Classroom. Haymarket Books, 2021.

Facing History & Ourselves. About Us, Facing History & Ourselves, 2022. Accessed 2 Nov 2022, https://www.facinghistory.org/how-it-works/our-unique-approach/our-pedagogy.

Hammond, Zaretta. Culturally Responsive Teaching & The Brain. Corwin, 2015.

Lemerond, Saul B. “Creative Writing Across Mediums and Modes: A Pedagogical Model.” Journal of Creative Writing Studies, vol. 4, no. 1, 2019. Accessed 16 Oct 2022, https://scholarworks.rit.edu/jcws/vol4/iss1/

Lerman, Liz and John Borstel. Critique is Creative: The Critical Response Process in Theory and Action. Wesleyan University Press, 2022.

Salesses, Matthew. Craft in the Real World. Catapult, 2021.

Stukenberg, Jill. “What Do Introductory Students Learn by Creating Shareable Digital Artifacts?” Journal of Creative Writing Studies, vol. 6, no. 2, 2021. Accessed 16 Oct 2022, https://scholarworks.rit.edu/jcws/vol6/iss2/

The Community of Inquiry. About the Framework: An Introduction to the Community of Inquiry, 2022. Accessed 5 Sept 2022, https://www.thecommunityofinquiry.org/coi

Wuest, Deborah A. and Prithwi Raj Subramaniam. “Preparing Trauma-Informed Future Educators. Strategies, vol. 35, no. 5, 202, pp. 16-20.

© 2023 by Mary Leoson, Finnian Burnett, & Jeffery Buckner-Rodas