by Jeffery Buckner-Rodas

Stories are a critical component of community. When engaging in storytelling, whether it’s through oral, written, visual, or other modes, we find ways to express who we are, learn what is important to us, and better understand those who came before us and who currently surround us. There are skills that can be taught in a classroom, but some, like taking a personal stance, self-advocating, owning one’s voice, and developing empathy are not so much taught as they are fostered within a nurturing educational environment. What you will find here are some of the techniques I use in my daily teaching practices as well as my personal views on the importance of the use of stories to help us see, understand, and sit with one another in a way that uplifts all involved.

I created this page and other components found in the Story-Based Pedagogy Project as part of the requirements of the Doctor of Arts in English Pedagogy program at Murray State University. This website includes the work of my colleagues Mary Leoson and Finnian Burnett. It is our desire to create a dynamic collection of resources to help educators in all areas of the world to find ways to include stories in their courses.

Context & Background

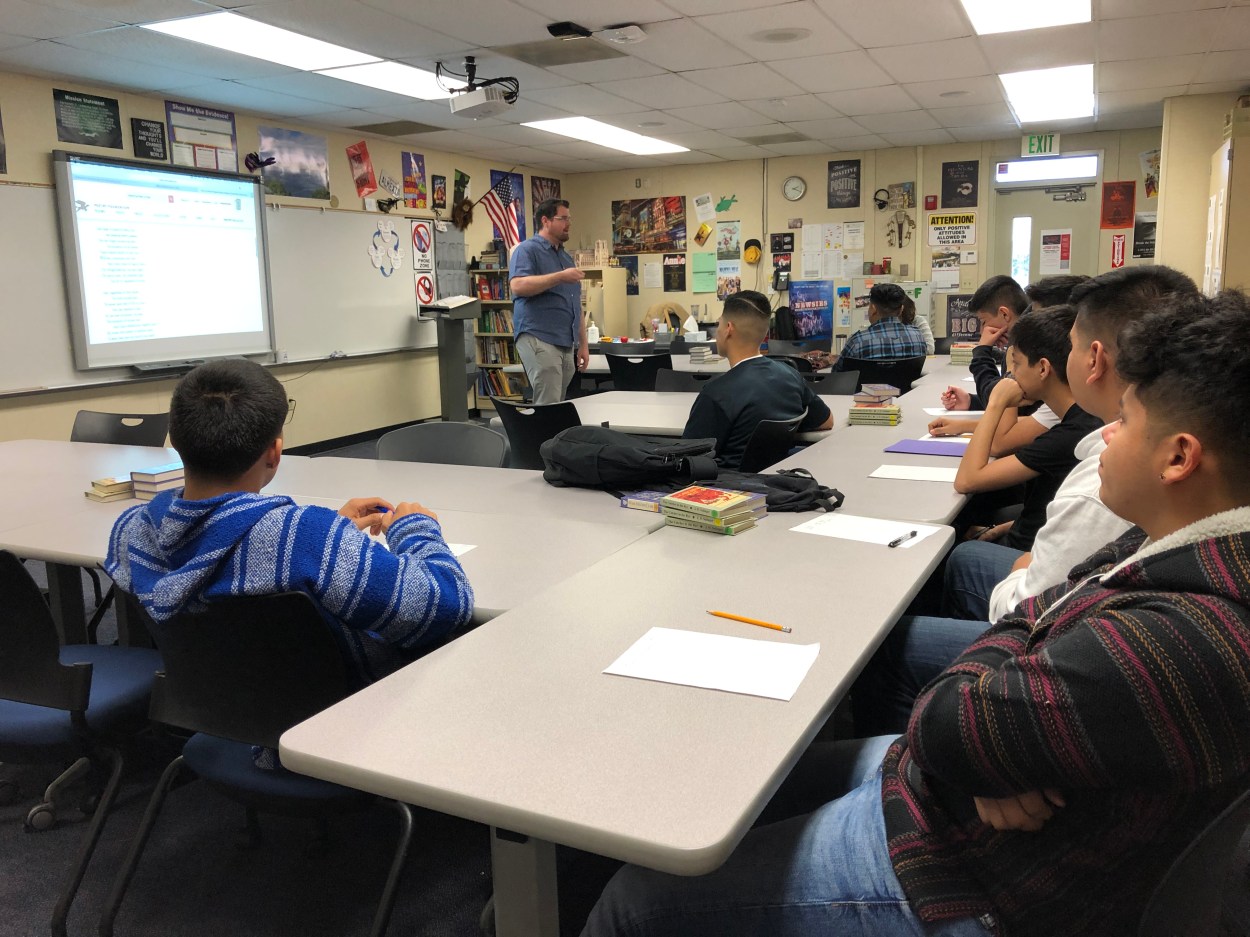

From the beginning of my time working in education, which began six years before I became a credentialed teacher, the use of stories in my learning units has been at the forefront of my efforts, regardless of the subject being taught. There are many reasons why this is my foundational approach, including the desire to reach as many of my students as possible while raising important questions that help us all to better understand what it means to be human and engage with the world around us. This goal is lofty, considering the diverse backgrounds, socio-economic struggles, varied interests, and considerably low performance patterns of the majority of my students. I spent most of my years as an educator working with students who, for various reasons, were far behind in credit completion and were sent to the district’s continuation high school, where they could earn credits more quickly and get back on track toward graduation.

Although these students were on the cusp of adulthood, it seemed that storytelling had, at some point in the past, become a ritual that trained them to go into a state of mind that flowed with the story, something I would describe as a return to a childlike state of wonder, perhaps even losing sight of their selves and their current environment. In other words, storytelling was something I could count on helping with student engagement.

Buckner-Rodas’ Research Question:

How can educators use process drama and story-based pedagogy to develop empathy and support culturally responsive teaching?

I consider myself to be a dramatist. I have been engaged in dramatic performances since the age of six, so perhaps the idea of bringing drama into other subject areas was not as difficult for me to do as it might be for others who do not have the experience. I saw a strong link between the use of storytelling, drama, and using the experiences and backgrounds of my students, what I later realized aligned with the practices of culturally responsive teaching (referred to henceforth as CRT). Even though I had not yet learned of the ideology of or studied the scholarship in the field of CRT, I had greater success in my lessons and a higher passing rate in my classes when I used these story-based and individualized strategies.

For example, I teach my students to come up with a story character on the spot, whether it’s a human being, animal, or object, and then they are asked to present a central conflict that this character must deal with. I guide the students to link that conflict with whatever real-world struggle we are currently discussing in class. These student-created stories, usually only a few sentences long, are written on a large poster, along with an illustration, and then placed on the wall of the classroom. As we discuss stories, articles, poetry, or real-world situations in the lesson, we tie the class-created character and scenario in to help the students draw connections between various sources of information. This practice allows me to prompt students to imagine themselves in a scenario and consider whether a central conflict relates to them in any way.

While using circle time—a period of three to five minutes in which we would sit in a circle and share ideas usually brought up by asking a question—and other drama-based activities in my junior-level ELA classes, it became clearer to me that I made many assumptions about my students and what I believed was a cause for their lack of credit completion. I was told my students were “at risk”, that they would do better with scripted lessons, learning packets, or a technical approach to education, a problem noted by Geneva Gay in Culturally Responsive Teaching (2018) that can lead students to place greater importance on academic achievement than on the protection of the cultural or ethnic identities. Along with the prescribed curriculum, I realized my own biases and assumptions interfered with ideas on how to proceed. As I worked to push those assumptions aside, as well as the robotic, scripted approach to teaching recommended to me, and allow for time to get to know my students through activities and conversations, I realized this is something that was not only allowing me to become more responsive to my students and their needs, but I also came to know myself in a more meaningful way.

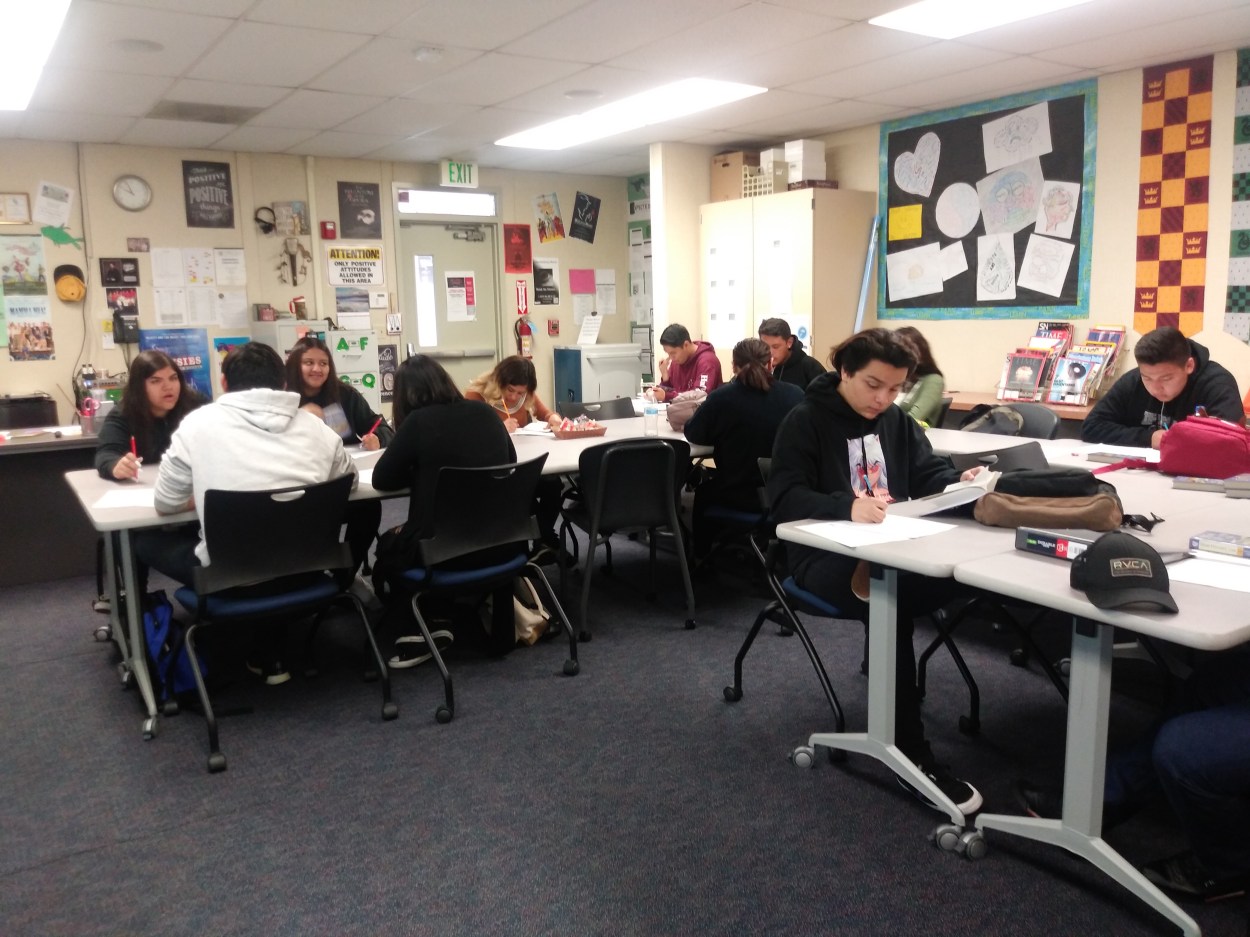

I listened to my students’ stories and insights on proposed questions during circle time and then sought out literature that would offer a way for the students to reflect on their own experiences while discussing the conflicts of characters or poetic narrators. This became a natural way for me to teach and engage with my students. Student-centered discussions during circle time, student-created stories, and improvised scene-like scenarios help the students engage with the thematic elements of the learning unit in ways that stretch them further than reading and writing alone would do. These approaches to story-based pedagogy allow for students to engage with the thematic elements of the learning units in a way that fosters empathy and allows for a culturally responsive approach to teaching.

Process Drama

The improvised, scene-like scenarios I use in my classes come from a methodology known as process drama. This method is distinguishable from theatrical performances that are rehearsed to be performed for an audience; the desire here is to have students interact with complicated issues in a way that pushes them to engage with improvised body movement and speech. CRT links directly to the use of drama because of the ability for students to create characters within scenarios that are based on their prior knowledge and experiences (Lee et al., 2015). Furthermore, students will bring their individuality to the space and analyze relationships of power while they reason and draw inferential and deductive conclusions. Their individuality will be in flux when engaged in dramatic play and they are provided with creative and critical opportunities to enter into each other’s worlds (Gallagher and Ntelioglou 2011) and consider multiple perspectives.

This synergistic play between prior and new experiences within multidimensional worlds of play is what process drama seeks to enhance by engaging students in life’s most complicated issues (Donovan and Pascale 2022). Process drama is interactive and engaging, and although it can be used to work through simple scenarios in a math or science class (think engaging with real-life scenarios and situations), it is also a way to allow students to consider complicated societal issues of the past and present. Students have a new sense of power as they take a stance and create a position of authority as they proceed in the drama (Bowell and Heap 2013). This empowerment comes by way of the necessity to make choices within this specific mode of communication. Real-world scenarios will sometimes require engagement with sensitive topics that must be approached with proper planning and care; in other words, they must be framed in a way to support constructive conversations that always foster greater empathy and understanding. Some examples of how to handle such topics are found below and in the theoretical framework linked to this project. Learning for Justice, formerly known as Teaching Tolerance, is a website full of resources to help support an inclusive classroom, including a discussion of process drama and its benefits. Also, check out the following video of Kristin Pedemonti who offers an excellent example of using storytelling and process drama in the classroom. What you will see is a training for teachers created for the Literacy Outreach Program in Belize.

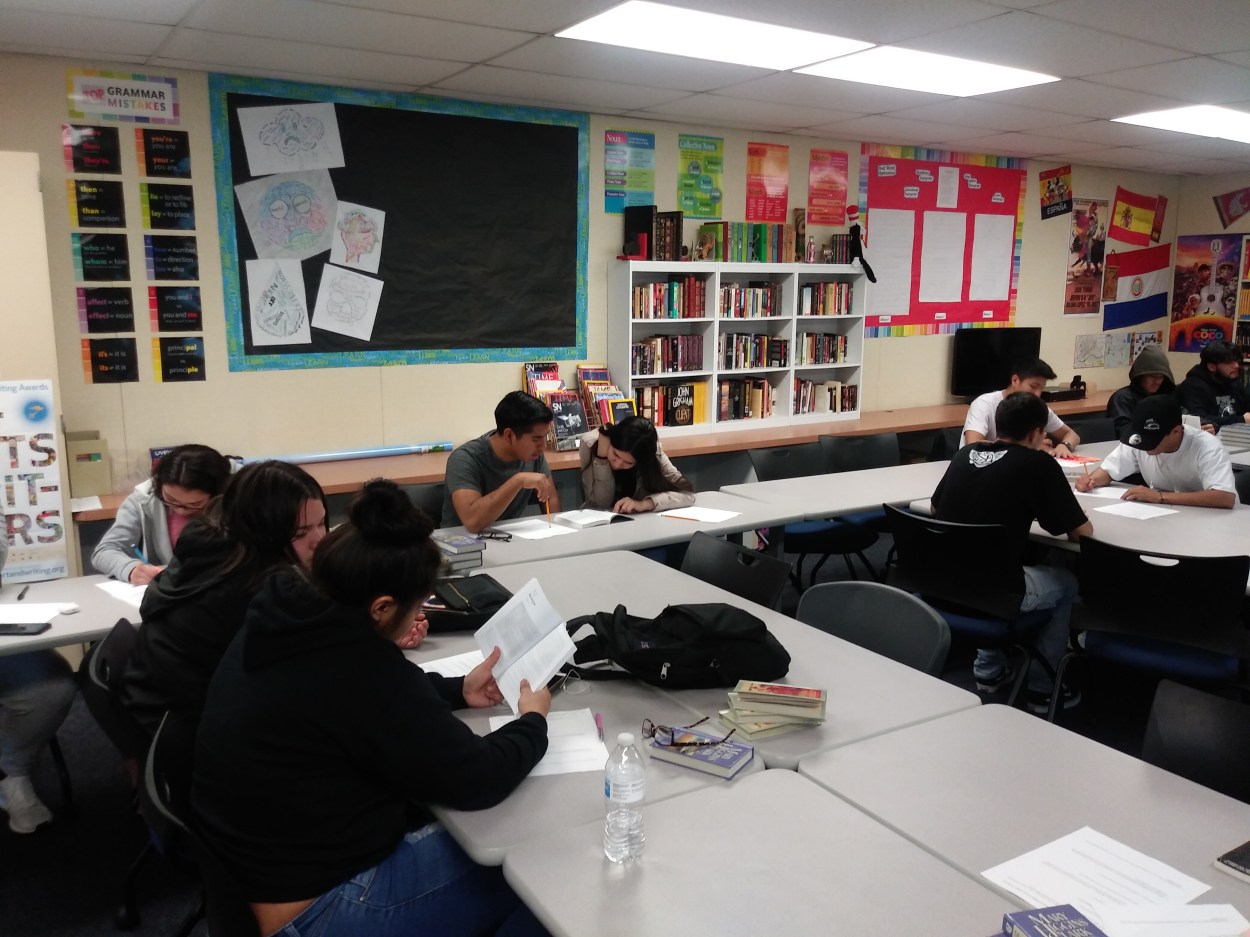

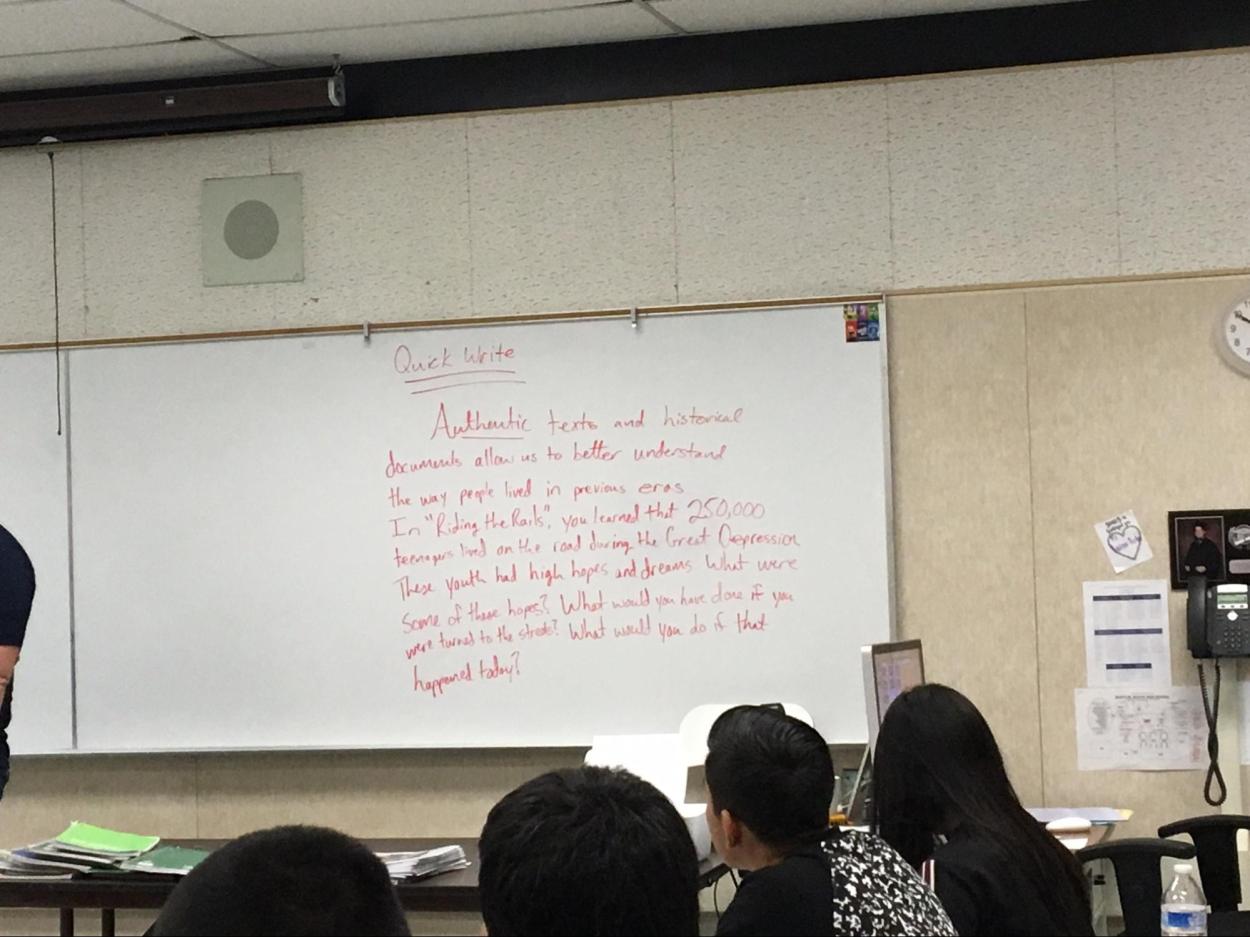

In a recent learning unit that used historical fiction and authentic texts regarding the Great Depression, I asked the students to consider reasons why teenagers would take serious risks to their health and safety by jumping onto moving trains. The students were on their feet and separated into groups of three when I gave them a prompt: You no longer have a place to call home…you’ve heard that others ride the rails to seek opportunities and fortune…where will the rails take you? After giving them a few moments to think, I asked them to speak as themselves, but pretending they were living in the 1930s. They verbalized in the present tense, stating their hopes and desires that led them to risk riding the rails.

After the students engage in improvisational discussions, they can be given a prompt to help them engage with their thoughts, feelings, and ideas on the situation through writing. The prompt in the picture reads:

Authentic texts and historical documents allow us to better understand the way people lived in previous eras. In “Riding the Rails”, you learned that 250,000 teenagers lived on the road during the Great Depression. These youth had high hopes and dreams. What were some of those hopes? What would you have done if you were turned to the streets? What would you do if that happened today?

It is important to remember that process drama does not ask students to imitate anyone’s behaviors, accents, movements, or cultural or ethnic backgrounds, nor should it be used as a reason to have students take on identities that are not their own, whether purposefully or inadvertently. Always keep in mind that this tool is about developing understanding and empathy. Students can consider the mindsets and decisions of others while remaining tied to their own identity. To avoid potential trauma, process drama must be properly framed.

For further resources on using process drama and other arts-based strategies in the classroom, read Putting Process Drama Into Action: The Dynamics of Practice by Pamela Bowell and Brian S. Heap (authors of Planning Process Drama), Integrating the Arts Across the Curriculum, 2nd Edition by Lisa Donovan and Louise Pascal, More Theatre Games for Young Performers: Improvisations and Exercises for Developing Acting Skills by Suzi Zimmerman, and Games for Actors and Non-Actors by Augusto Boal. Also, see Drama Based Instruction: Activating learning through the arts, a webpage provided by the University of Texas. There is also an expanded discussion of the use of process drama in my literature review and theoretical framework document, which is found below.

The Monologue Project

A major part of my research for this project led me to create an example of how to use real human stories to deepen our connections and understanding of one another. This monologue project, based on the work of Ann Frkovich and Annie Thoms (2004), is different from the use of process drama, so all related information, documents and files can be found here.

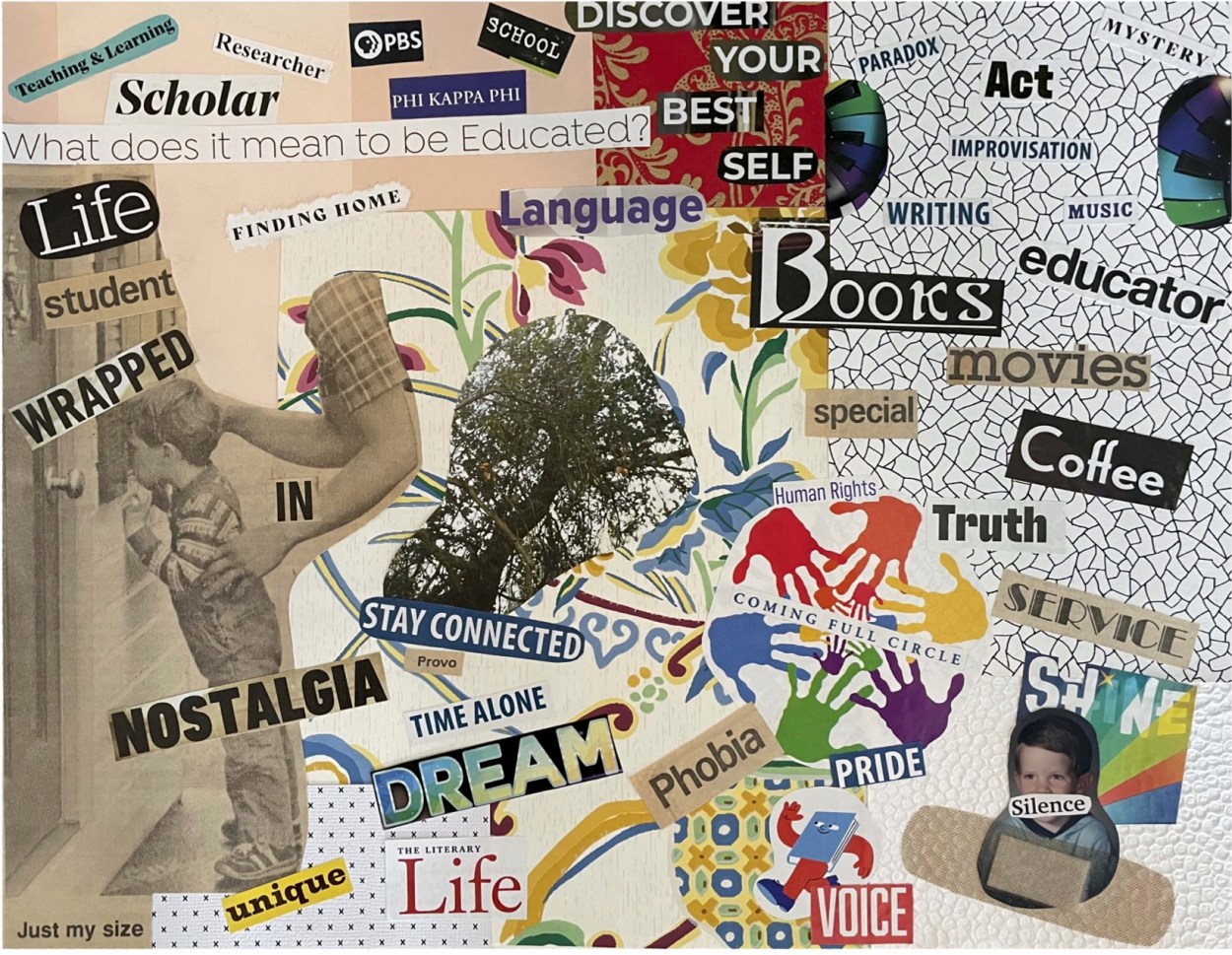

Buckner-Rodas, Jeffery. Positionality Art: My Self in 2022.

Buckner-Rodas’ Positionality Statement

The use of culturally responsive teaching practices in the classroom not only requires that I get to know the cultural backgrounds of my students. In order to find ways I can be supportive of student success and maintain a positive teaching environment, I must also work to better understand my inner self, my place in society, and my past. It is my desire to make this a continual process. In the Power of Story section of this website, you will find my digital story, which is one process of creation I have used to better understand myself and how I connect with story. Creating the above art helped me to consider my strengths, discover hidden biases, and reflect on how I fit into society. Existing as a small part of a much larger whole, it is important for me to learn from others as I shine my light so that others have the opportunity to learn from me. This is also a continual process of reflection and consideration.

Engaging with story, identities, cultural backgrounds, hopes and fears in the classroom means that those involved will likely have to confront current or past traumas. I myself have experienced trauma in the classroom, and though my experiences may differ from those I teach, I am certain that we can approach one another in ways that will foster compassion, empathy, and that will deepen connections. Engaging in self-discovery, teacher inquiry, and reflecting on positionality allows for opportunities to create a better learning environment in which all involved can find ways to connect, heal, and grow. I cannot possibly know exactly how to handle each student and situation, but the more I know myself, the more opportunities I will have to get things right.

Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

View as a Flipbook from Heyzine: Theoretical Framework Flipbook

Download as a PDF file: Theoretical Framework PDF

Works Cited

Ann Frkovich & Annie Thoms. (2004). The Monologue Project for Creating Vital Drama in Secondary Schools. The English Journal, 94(2), 76-84. https://doi.org/10.2307/4128778

Bowell, P., & Heap, B. S. (2013). Planning process drama: Enriching teaching and learning. Routledge.

Donovan, L., & Pascale, L. (2022). Integrating the arts across the Curriculum. Shell Education.

Gallagher, K., & Ntelioglou, B. Y. (2011). Which New Literacies? Dialogue and Performance in Youth Writing. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 54(5), 322–330. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41038865

Gay G. (2018). Culturally responsive teaching: theory, research, and practice (Third). Teachers College Press.

Lee, B. K., Patall, E. A., Cawthon, S. W., & Steingut, R. R. (2015). The Effect of Drama-Based Pedagogy on PreK–16 Outcomes: A Meta-Analysis of Research From 1985 to 2012. Review of Educational Research, 85(1), 3–49. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24434331

“Process Drama: Bullying.” YouTube, uploaded by Kristin Pedemonti, February 11, 2012, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cAJ-yVi1Izw.

Teaching tolerance – learning for justice. (n.d.). Retrieved January 11, 2023, from https://www.learningforjustice.org/sites/default/files/2018-03/TT-Podcast-Transcript-Footsteps-of-Others-March2018.pdf

© 2023 by Mary Leoson, Finnian Burnett, & Jeffery Buckner-Rodas